Water, covering two-thirds of the earth’s surface and permanently inundating nearly 4% of the global land mass, is a ubiquitous element. It undergoes a continuous cycle within the hydrosphere, evaporating from the earth’s surface, condensing in the atmosphere, and returning as liquid water. Despite its abundance, water scarcity is a common issue, particularly in regions with uneven distribution. While some places are well-watered, others face shortages, exacerbated by the increasing global population. Although the earth will not run out of water, variations in water quality persist. The majority of the earth’s water is too saline for human use, and pollution from human activities has further degraded the quality of fresh water, diminishing its utility. Even though evaporation serves as a natural water purification process, salts and pollutants left behind continue to contaminate the returning rainwater. Life in all its forms relies on water, making it a vital resource with complexities and challenges that must be addressed [1].

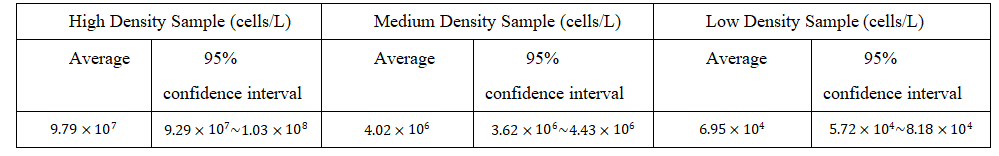

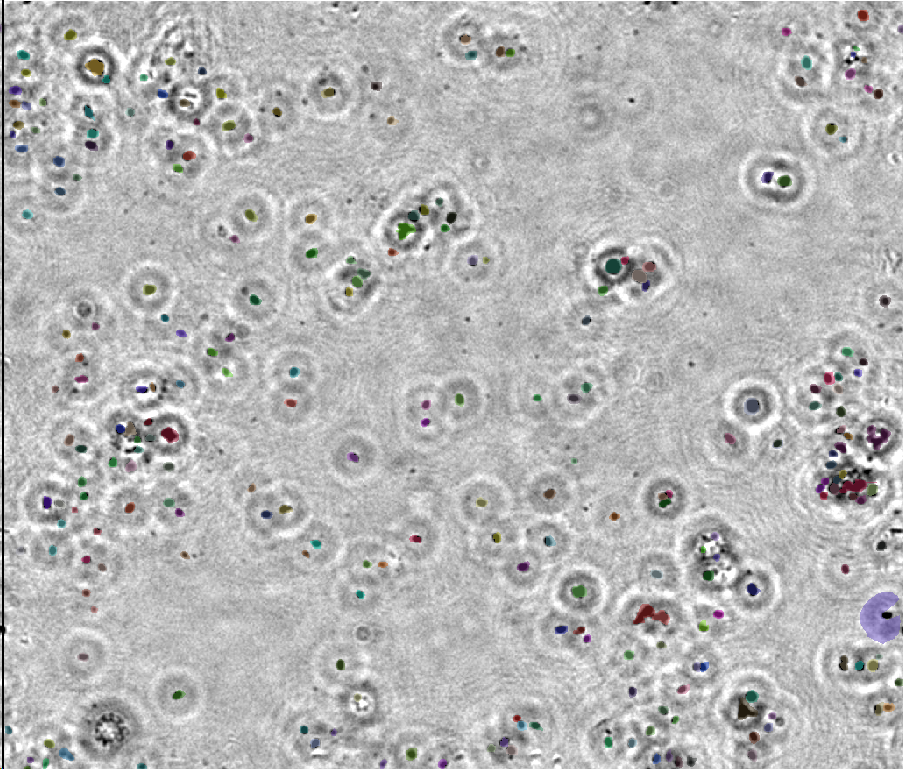

However, with the continuous advancement of industrialization and urbanization, limited water resources is also facing an increasingly serious risk of pollution. For example, on February 3, 2023, a train derailment in Ohio released toxic chemicals into the environment, causing significant water contamination for local residents. Therefore, the detection of water quality has become particularly important. The interconnectedness between the living water environment’s quality and underwater plankton is significant. Stable physiological characteristics, species, and numbers are exhibited by indigenous plankton in various waters. Swift responses to changes in the water body are observed in these organisms. When the water quality experiences pollution to different degrees, variations in plankton species occur due to differing bacterial densities in the water. Optimal water quality is distinguished by moderate pH values, high oxygen content, and low bacterial and microorganism content. In such conditions, higher oval algae, diatoms with columns, and corresponding zooplankton can thrive. Conversely, poor water quality accommodates organisms like sandshell worms, cyclopia, and algae-tolerant strong plankton. Severe water pollution results in high bacterial density, posing a challenge to the survival of most plankton. Only species with stronger pollution tolerance, such as nudibranchs, cyanobacteria, and caecilian earthworms, can endure. Therefore, examining underwater plankton species and quantity allows one to gather information about water quality and its trends, either directly or indirectly.

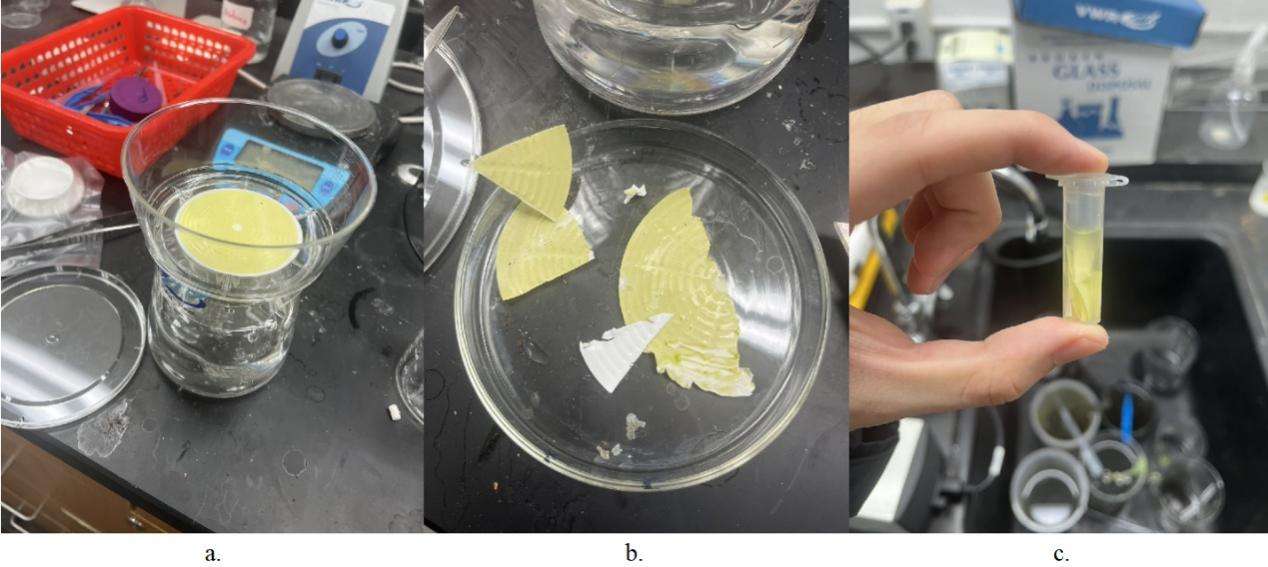

Observation forms the basis for many existing techniques in detecting underwater plankton. Initially, underwater plankton observation relies on a sampling approach. This involved using a sample collector or trawl at a specified water sampling site, and then transporting the sample to the laboratory. Subsequently, the sample underwent a certain degree of treatment, was fixed, and was preserved into observable slide samples. Finally, a laboratory microscope was employed for observation and identification. While sampling observation yields relatively abundant underwater plankton morphology data and reduces identification errors, it comes with notable drawbacks. The process of sampling, transporting to the laboratory, and studying the experimental results introduces significant delays, hindering the timely acquisition of large-scale experimental data for monitoring water quality pollution conditions. Therefore, the traditional sampling-based observation method falls short of meeting the current demands of underwater plankton research and development. To address this, the study of obtaining effective underwater plankton data on a large scale, both temporally and spatially, through relatively simple operations has become a crucial research focus. As multidisciplinary research gains momentum, researchers are increasingly exploring detection methods and tools from other disciplines. Techniques and tools from diverse fields, including biology, acoustics, optics, and electronics, have garnered attention and been integrated into underwater plankton detection research. One such noteworthy approach is the optical detection-based digital holographic imaging method, which stands out for its accuracy, comprehensive experimental data, and effective visualization of results, attracting the interest of experts and scholars with its broad research outcomes and application scope.

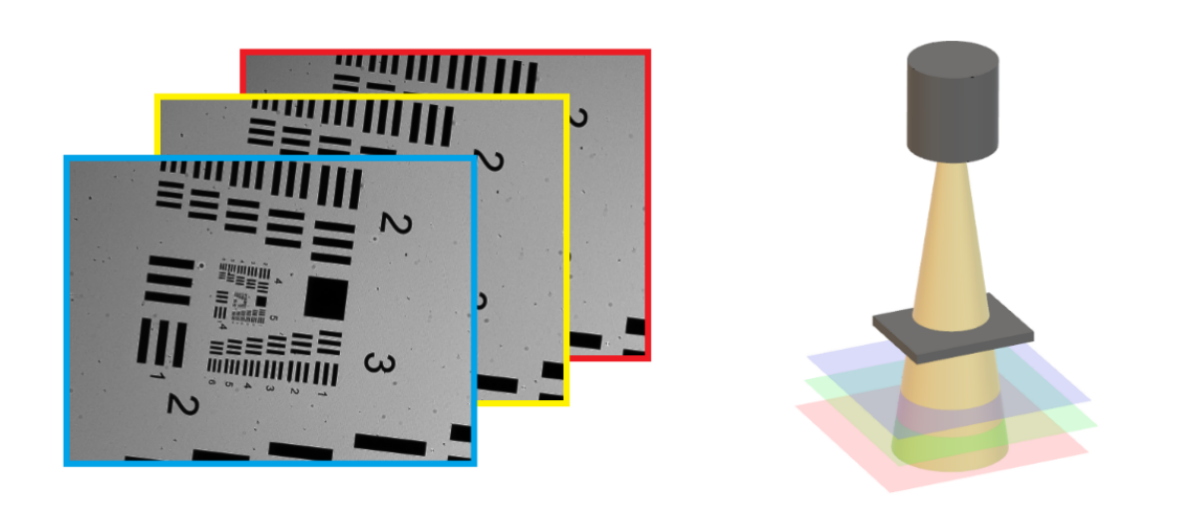

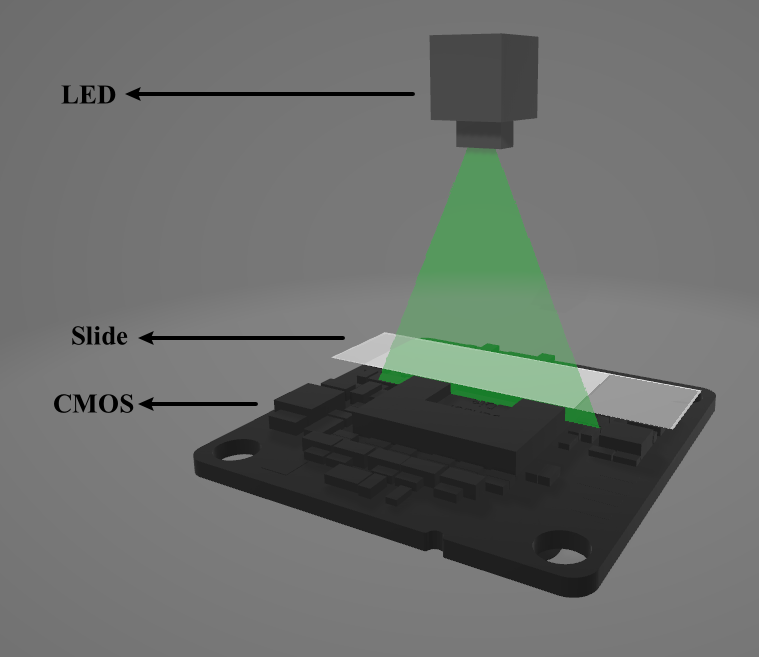

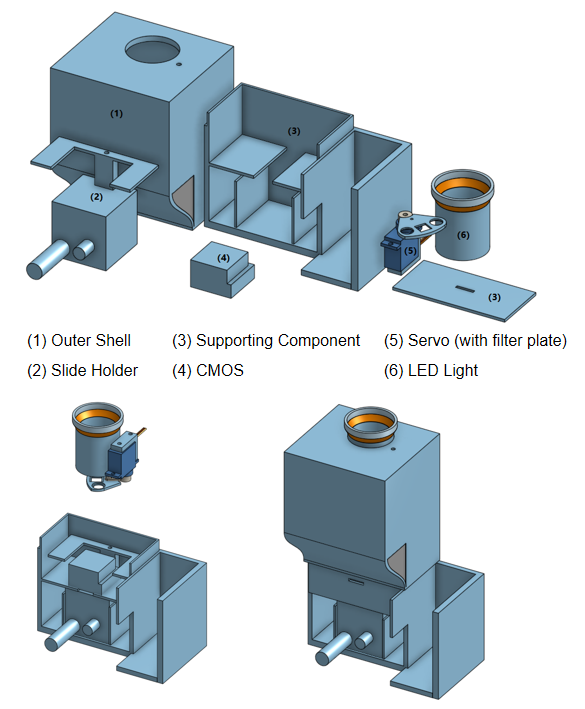

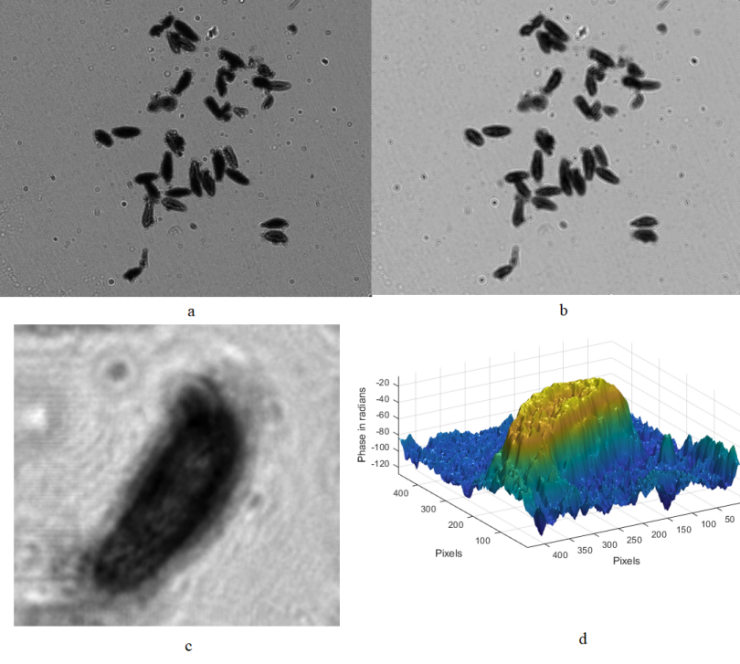

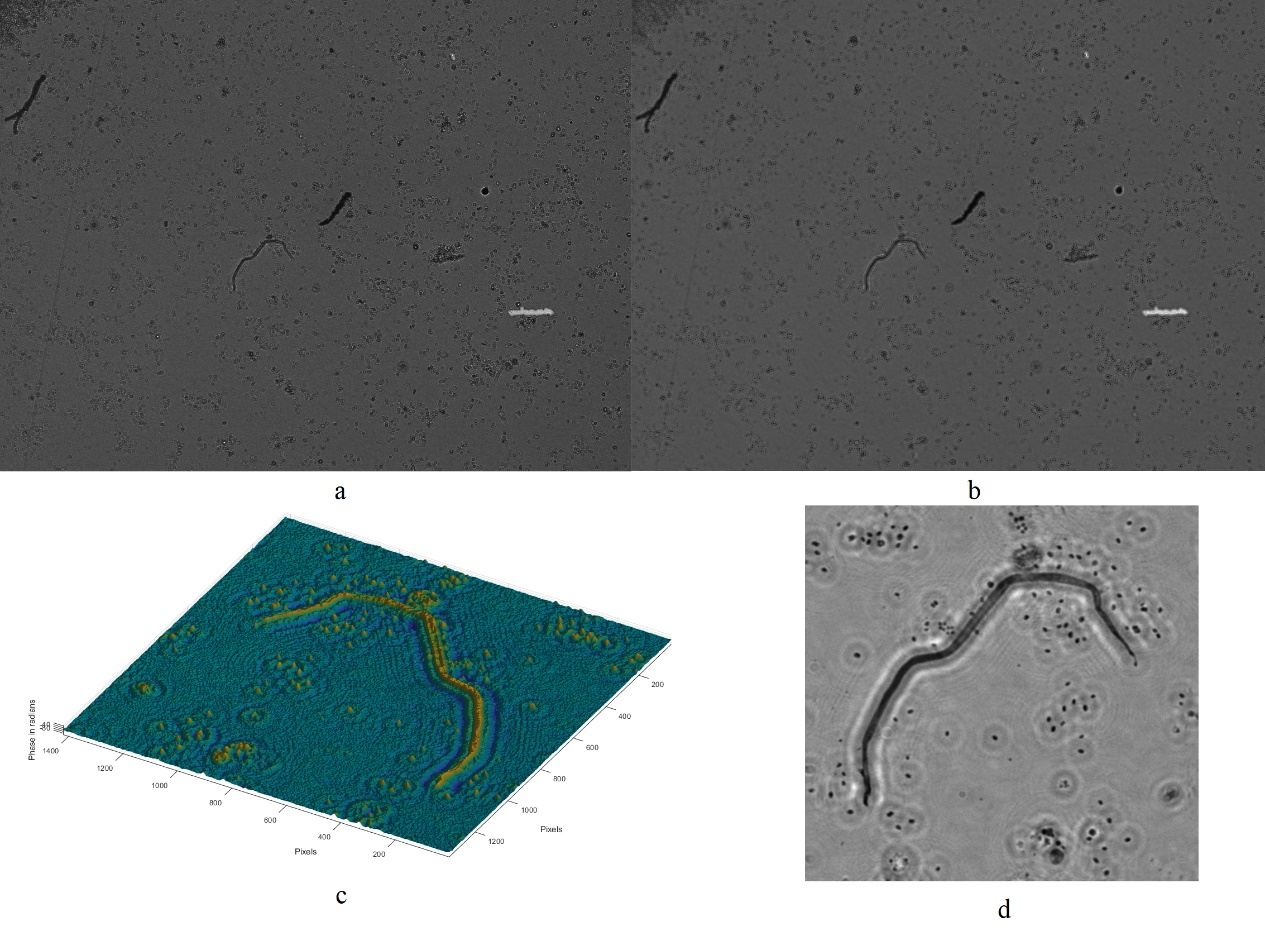

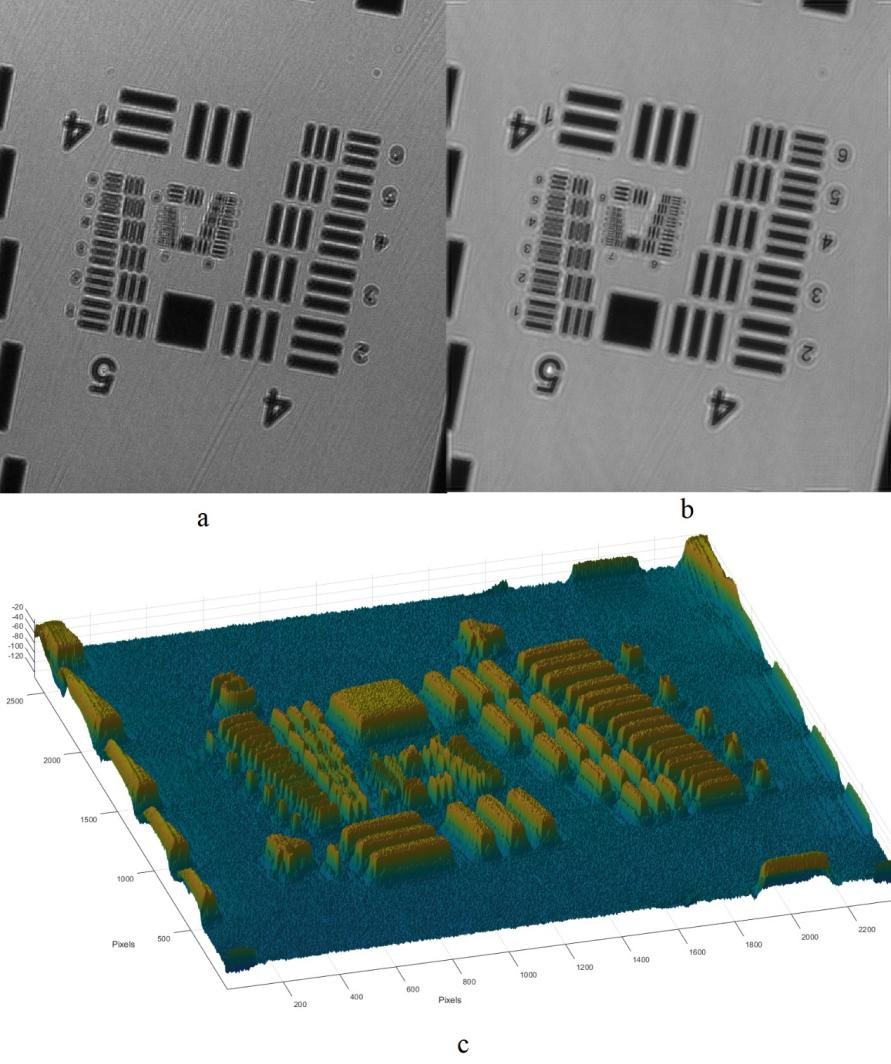

Digital holographic microscopy (DHM) [2] is a widely adopted technique that enables the recording and reconstruction (via the digital holographic principle [3]) of an optical field modulated by various factors such as scattering, refraction, absorption, and reflection from a biomedical [4] or technical micro-object. Hologram demodulation techniques, including Fourier Transform [5], spatial carrier phase shifting [6], or Hilbert Transform [7], along with more precise multi-frame techniques like temporal phase shifting, can provide complex data at the registration plane. The reconstructed complex data contains information about amplitude (absorptive features) and phase (refractive features), which is crucial for label-free quantitative imaging. Over the past two decades, quantitative phase imaging has emerged as a leading framework for label-free live bio-specimen examination [8]. Post-reconstruction, numerical propagation of the optical field to the focus plane is achievable, for instance, using the angular spectrum (AS) method [9], especially when the hologram was captured outside the focus plane. The determination of the focus plane often involves automatic methods like autofocusing approaches [10], now also integrated into deep learning frameworks [11]. Quantitative phase microscopes following DHM principles, as well as traditional bright-field microscopes, are typically bulky with multiple optical elements. In contrast, lensless digital holographic microscopy (LDHM) [12], based on Gabor in-line holography [13], consists of a light source, a CCD camera, and a sample placed between them, preferably near the CCD matrix [14]. This configuration ensures a large field of view (FOV) primarily dependent on the size of the CCD matrix. Resolution in LDHM is mainly limited by the pixel size, requiring it to be small enough to capture dense Gabor holographic fringes without optical magnification [15]. The total number of pixels sampling the hologram is crucial for information bandwidth and resolution.

The recent advancement of lensless imaging owes much to the mass production of affordable digital image sensors with small pixel sizes and high pixel counts [16, 17], alongside improvements in computing power and reconstruction algorithms for processing captured diffraction patterns. Compared to conventional lens-based microscopy, lensless approaches offer key advantages, including a large space–bandwidth product, cost-effectiveness, portability, and depth-resolved three-dimensional imaging. These advantages make lensless imaging particularly suitable for analysis applications requiring extensive statistics, such as cytometry for “needle-in-a-haystack” diagnostic tasks like the Papanicolaou smear test for cervical cancer [18] and blood smear inspection for malaria diagnosis [19]. Lensless imaging is well-suited for studies demanding statistically significant estimates based on limited samples, as seen in the examination of thousands of sperm trajectories to identify rare types of motion [20] and the performance of a complete blood count [21]. Applications with varying number densities, such as air and water quality tests, benefit from lensless imaging’s large space–bandwidth product and depth of field. Lensless imaging is also an excellent choice for point-of-care and global health applications, where compact, portable, cost-effective, and widely distributed devices and approaches are essential. Unlike traditional microscopy, lensless imaging doesn’t require expensive precision microscope objective lenses and light sources. In many instances, individual light-emitting diodes suffice for illumination, and the most expensive component is the image sensor, which can be as low as a few tens of dollars due to mass-produced complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor image sensors for mobile phones [16, 17].